Managing risk connectivity in a business interruption

By Sean Mooney

executive editor, StrategicRISK

Both the severity and frequency of BI claims are increasing, primarily due to growing interdependencies between companies, the increasing complexity of supply chains, and the drive for ever-leaner production processes. Interdependencies between suppliers can cause great uncertainty, a situation that is compounded by the dependence of many businesses on key suppliers. There is an increasing concentration of production sites and logistics hubs in certain areas, and if these are hit by a disruptive event, losses can spread to multiple organisations around the globe.

In short, the world has become more interconnected while at the same time more and more activities are being outsourced to third parties, points out regional director of JLT Risk Consulting Asia, Craig Paterson. “Therefore, any interruption in operations (both own and/or third parties) could seriously impact survival, especially in competitive markets where customers need their products and services immediately,” he warns. Indeed, BI exposures are largest for sectors with high levels of interconnectivity and technological values, as well as concentrations of risks in single locations such as automotive, semi-conductors and power and petrochemical plants.

The results of Aon’s 2017 Global Risk Management Survey reflect the growing concern about these issues, with BI ranking in the top 10 risks globally (eighth). Interestingly, BI was ranked as the fifth highest risk in the Asia-Pacific region. This should come as no surprise, because as manufacturing production continues to shift to Asia, so too have large claims. Participants in the aviation industry, which is vulnerable to interruptions caused by inclement weather conditions, computer glitches, mechanical problems, terrorist attacks, power outages and unruly customers, rated BI at number two. The same ranking was registered for the lumber, furniture, paper and packaging sectors, which depend heavily on natural resources and weather.

Different threats, same impacts

Non-natural hazards such as human error or technical failure are at the root of most BI claims, with fire and explosion, machinery breakdown and faulty design or manufacturing the main culprits. Add to these a rising number of natural catastrophes such as storms and floods and the newest challenge, cyber threat. These can shut down assembly lines, cause electric outages, block customers from placing orders, and break the equipment that companies rely on to run their businesses. All these threats have the same type of impact, as JLT Risk Consulting Asia’s Craig Paterson points out. “They can disrupt operations, damage markets and cause both physical and financial loss,” he says. “While each has its own particular characteristics, ultimately they can all seriously impact a company’s ability to survive.”

In an ever increasingly complex world in terms of connectivity, interdependence and data, risks for individual businesses are evolving, adds Willis Towers Watson’s head of forensic accounting and complex claims, Asia, Henry Dumas. “Today’s BI risk is different from yesterday’s (take the effect of just-in-time supply chains, globalization and the reliance on networks) and it will be different from tomorrow’s,” he explains. “Aside from technology impacts, we have the topical issues of climate change and terrorism. The point being that new BI risks may not always be evident. They may only be realised once a significant event happens, e.g. integrated supply chains in a localized area heavily impacted by the Thai floods. They are then aggregated by interconnectivity throughout the world between corporations.”

Dumas says that there are many different risk events can lead to a BI claim. He gives as an example of natural catastrophe the hurricane that ripped through Puerto Rico in September “decimating hotels, roads and local attractions resulting in a large drop in tourism”. As for a man-made disaster, it’s hard to go past the chemical explosion in the port of Tianjin (see case study), which resulted in “damage to property and disruption of supply chains”. A good example of power interruption might be an “external power failure to an aluminium smelter causing all liquid metal work in progress to solidify and the plant unable to operate” Dumas adds, while a recent cyber-attack involved the “hacking of a Ukraine power station, systems accessed remotely and operator losing control, leading to BI losses”.

‘New and disruptive business practices’

UK-based managing director of Marsh’s risk finance practice Caroline Woolley points out that when it comes to BI, new and disruptive business practices demand new solutions. “With so much reliance on third parties with a global spread, and a complete integration of technology in business processes, the risks that companies face are increasing and broadening, she says. “Whether it is a natural catastrophe event or a cyber-attack, the impact on a business can be devastating and its whole survival can be threatened. There is an expectation that businesses do everything they can to become resilient, through loss prevention, risk assessment and business continuity management.”

These high expectations mean customers and shareholders alike have a low tolerance to any interruption of service, or income. Woolley again: “Once risks have been managed as far as possible, the next step is to insure the risk, allowing business interruption policies to pay for mitigating actions and increased costs following an event, and also to pick up any loss of income, she says. “Clients don’t want to buy a different insurance policy for each BI risk they face. The insurance industry needs to take this holistic view of business interruption to ensure there aren’t any gaps in cover.”

| MORE READING The RIMS Business Interruption Survey 2017 was distributed to RIMS members in late 2016. Up to 20% of the 372 respondents did not know whether their policy provided any coverage for cyber risk, supply chain disruptions, widespread damage/natural catastrophe, and non-physical damage events. This is concerning, given these events’ high potential to significantly disrupt business for long periods of time. |

.

| MORE READING The Swiss Re Institute sigma study No 2 /2017 ‘Natural catastrophes and man-made disasters in 2016: a year of widespread damages’ makes for interesting reading for those trying to put BI into some kind of global perspective. In total, there were 327 disaster events in 2016, of which 191 were natural catastrophes and 136 were man-made. At USD175 billion, total economic losses from disasters in 2016 were the highest since 2012, and a significant increase from USD94 billion in 2015. As in the previous four years, in 2016 Asia suffered higher economic losses due to natural and man-made catastrophes than any other region of the world. Economic losses from disaster events in Asia were an estimated USD83 billion in 2016, of which approximately USD9 billion were covered by insurance. Global insured losses from catastrophes were also the highest since 2012, at around USD54 billion in 2016, up from USD38 billion in 2015. The implication of the increase is that many tens of thousands of policyholders in disaster events benefitted from having insurance cover in place, to receive speedy indemnification for their property losses, get their businesses back up and running quickly, and mitigate other economic and humanitarian hardships. |

Connect the dots to be resilient in today’s dynamic world

|

|

Business disruption, business interruption, reputation damage… these outcomes from risks that turn into events are commanding an increasing amount of attention in the private and public sectors. This is occurring as we continue to see examples of highly disruptive, high-profile events that have cost organisations dearly, in many ways. This ‘spider’s web of risk’ can cause major business interruption and disruption, and require risk professionals to put appropriate resilience measures in place.

Organisations across the board, in both the private and public sectors, exist in an ecosystem that is ever more open, porous and dynamic. The need for all organisations to anticipate and adapt to changes in their fluid ecosystems – and to have good business resilience measures in place to respond to negative events in these ecosystems – is arguably more important than ever. In this interconnected and increasingly digitised world, many risks and uncertainties that we contend with cannot be evaluated and managed by themselves in isolation to other risks and events. Living in an interconnected world means that we need to look at the interconnected and systemic nature of impacts of a web of connected risks, and the speed at which these risks, in various combinations, could impact our ability to achieve our objectives.

Sky-high costs

A recent real-world case in which one risk eventuated and led due to a series of connected risks is the major IT network failure at British Airways in May 2017. This was a very expensive global disruption to the airline’s business. Estimates of the cost are generally agreed to be between USD110-190million, not including the reputation damage and hard-to-estimate potential loss of future business. The outage, over three days, caused almost a third of flight bookings to be cancelled, some 750 flights around the world. Thousands of passengers were stranded. The error has been attributed by the company to an IT technician who made an error in shutting down a power supply and then tried to restore it in an “uncontrollable manner”. The combination of a series of cascading failures meant that BA’s operations were severely disrupted.

As well as the financial costs, the reputation impact was very damaging for the airline and its parent company, IAG. Was this incident preventable? Yes. Could it have been handled better? Yes. Has it happened before to an airline where lessons could have been learnt? Again, yes. Would understanding the risks in an interconnected network and going through scenarios help to ensure appropriate resilience is in place to safeguard against such impact? We would like to think so.

Some common features about interconnected risks and uncertainties (remembering that we are talking about upsides as well as downsides) are as follows:

1. They have multiple characteristics, causes and consequences;

2. A collection of risks when combined together can result in new risks or outcomes;

3. Risks can spiral and morph in unpredictable ways.

It can be difficult to see a full 360-degree view of how circumstances and changes in our ecosystem can influence the way that multiple risks could eventuate. The cause(s) of risks turning into events are often separated from the symptoms, which shouldn’t be the case because you need to understand the symptoms to treat the weakness.

Understanding the interconnectivity of the risks in our ecosystem can be achieved in a number of ways, and it doesn’t need to be complicated. This is a one way to look at it:

1. Take a practical approach to understanding risk interconnectivity through systems and networks thinking;

2. Ensure you have good resilience practices in place, such as following the principles of high reliability organisations and proper stress testing;

3. Maintain awareness of threats through transparency, clarity and information sharing across your ecosystem.

A web of connections

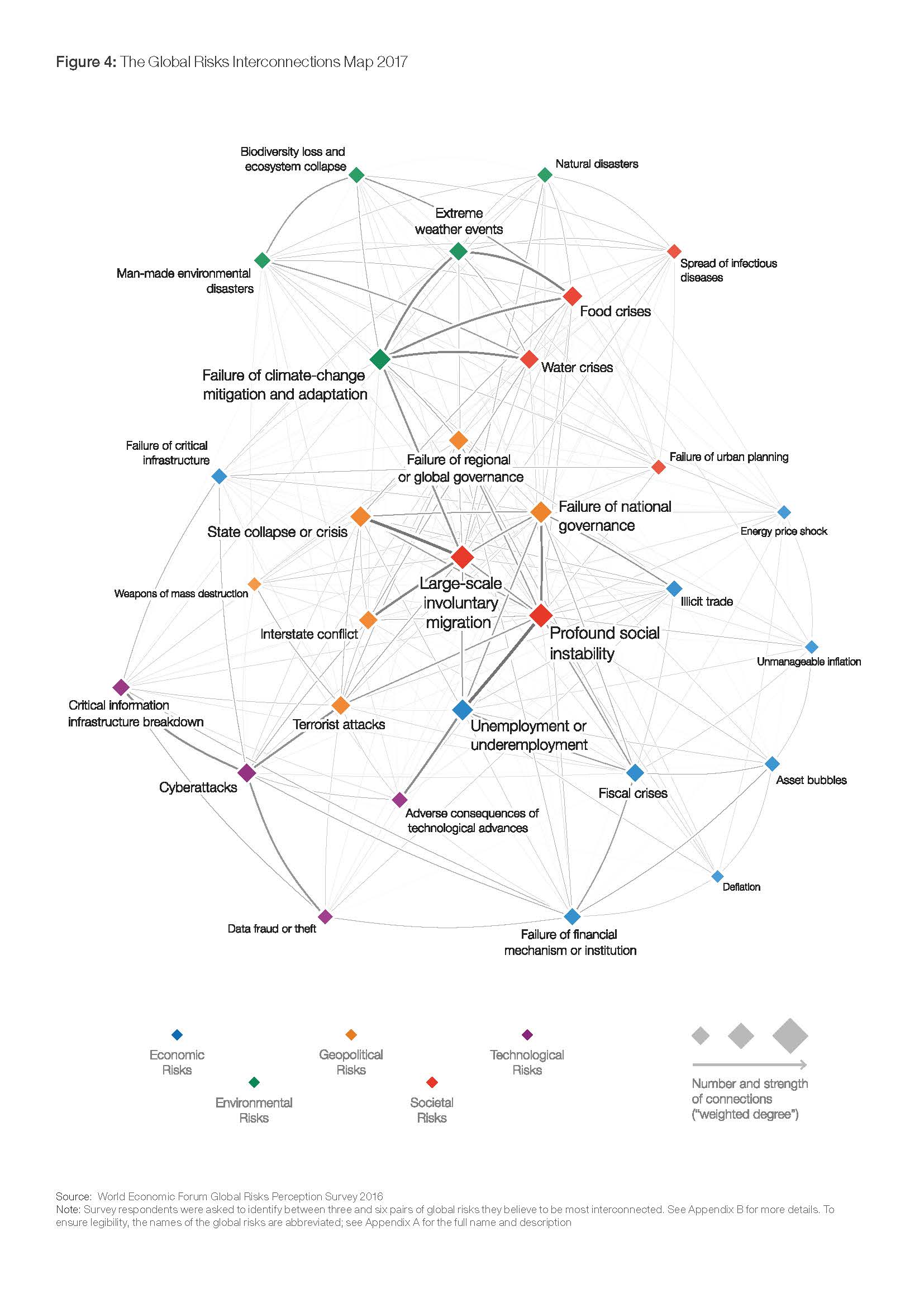

Does the classic ‘impact and likelihood’ risk matrix give us enough context in today’s interconnected world? Maybe we now need an additional factor, of ‘connectedness’. Risks that, individually, are rated as minor or moderate at best on a risk heat map can have an amplified effect when they are key nodes or drivers in a network of risk and uncertainty. A Risk network is like a spider’s web of connections. Understanding how this web responds to change, and its pressure points, can help us understand the best resilience measures to focus on.

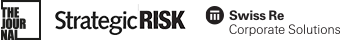

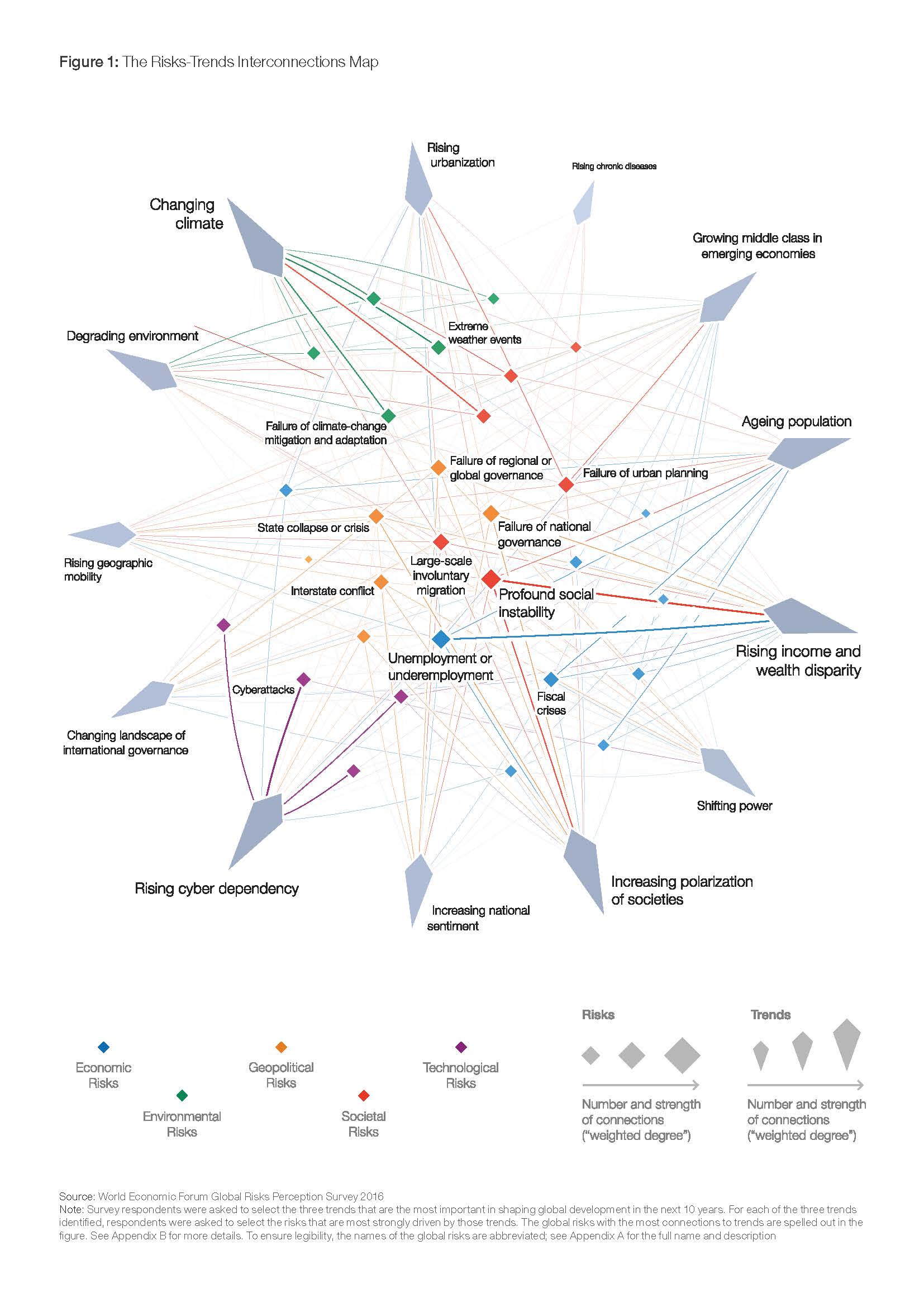

For a global example of viewing interconnected risks in a “map view”, consider the following maps in the World Economic Forum (WEF) Global Risks Report 2017 (source: The Global Risks Report 2017, World Economic Forum, Switzerland, 2017).

Enlarge

Enlarge

These examples from the WEF are, of course, at a global level. Do you have a map of interconnected risks for your organisation and its ecosystem, or your region, functional area, department and/or project? Networks theory is nothing new in commerce and industry; it has been used for many years for various purposes. If you do not yet have a risk network map, you could create one by bringing together appropriate people in a facilitated workshop. Once risks are identified and mapped to each other, you can review the effects of different scenarios occurring, to test and understand how you would respond to maintain resilience.

When you draw a network map of interconnected risks, look for the following patterns: (see diagram below)

• Key nodes (risks) in the network that link many other nodes together

• Key drivers (green node) in the network, that directly relate to many others and links groups

• Gaps, where risks appear standalone

Enlarge

Organisational resilience

We need to ensure we have organisational resilience to anticipate and respond to changes in our ecosystem. But what does ‘organisational resilience’ mean in practical terms? One model to think about is that of a high reliability organisation. The characteristics of an HRO apply to all types of industries and the public sector.

At a high level, an HRO typically has the following traits:

1. There is a focus on highly trained people and reward systems that reflect their abilities, and people are trained in how to deal with a high-stress crisis environment;

2. There are frequent process audits and continuous improvement efforts (on controls, processes, technology solutions, etc.) occur as “business as usual”;

3. There is a widely distributed sense of responsibility and accountability for reliability, for thinking through risks and possible failures, and for ensuring there is the right level of redundancy (with appropriate controls) in place;

4. There is an ethos of checks and counter checks as a precaution against potential mistakes is part of the organisational culture;

5. When a crisis situation occurs, people come together quickly and in a concerted manner to manage the situation; they have been trained to deal with such situations and on how to act under intense pressure.

A way to test and measure your resilience is to conduct stress testing against scenarios. The banking and finance sector is often held up as good practice in this regard, particularly since the 2008 global financial crash. The military is another good example of stress testing, through the conducting of varied training exercises. The point with stress testing is not to try to predict exactly how events can and will unfurl, for we cannot see into the future. Rather, it is to see what the implications of a range of scenarios will be, to test how resilient you are, and whether you should address certain weaknesses and symptoms that are uncovered as vulnerabilities, as well as understanding the elements that add the most value to taking different risks.

Trusting and transparent relationships

To best anticipate and adapt to interconnected risks, and to see upcoming changes to your ecosystem ahead of time, you need open, trusting and transparent relationships with every important stakeholder in your ecosystem. With such a foundation in place, the work you do to understand the interconnectivity of risks and the implementation of resilience measures will be most effective.

For example, let’s consider one element of your ecosystem – ethics and social responsibility in working practices across your supply chain. We want complete transparency and trust that good ethical practices are in place and being followed in all organisations we work with. To have confidence about this, and to verify it through appropriate assurance activities, we must have trusting and transparent relationships across our ecosystem of suppliers and customers, including those that are several levels removed directly from us (for example, sub-sub-suppliers and contractors). This requires good communications and management systems.

In today’s modern and dynamic (and increasingly digital) global environment, organisations exist in an ecosystem of relationships. Taking the time to truly understand the interconnections between your risks and uncertainties (upsides and downsides), and ensuring that you have appropriate, stress-tested resilience measures in place to safeguard value, plays an important role in protecting not just your organisation, but also many others that exist in your ecosystem.

Sean Mooney

Sean Mooney is the Asia-Pacific executive editor of StrategicRISK. Prior to this he was the Asia-Pacific launch editor.

Gareth Byatt

Gareth Byatt is principal consultant, Risk Insight Consulting and has more than 20 years of experience in international Risk Management and Project Management. He has been a Head of Risk and Head of a Global IT PMO, and has managed international programs and projects in Construction, Oil & Gas and IT. Gareth is based in Sydney, Australia and has also worked in London, Paris and Singapore. He holds an MBA and a First Class Honours degree. He is a frequent speaker at international conferences on Risk and Project Management, and has authored and co-authored over 50 articles, which have been published internationally.

Neil Allen

Neil’s passion is to use applied systems thinking to unlock potential and provide insightful and holistic interventions for clients to improve sustained performance. He arrived in Sydney after spending 12 years running a successful risk management consultancy in the UK. Neil is a founder and fellow of the Bristol University Systems Centre and is now a visiting academic at the universities of Bristol (UK), Canterbury (NZ) and Bath (UK)